Names of the Women - a Review

- Chris Maunder

- Apr 15, 2021

- 7 min read

I was excited when Natalie told me about a novel published very recently, Names of the Women by Jeet Thayil. This is subject matter on which I would write a novel myself if I thought I could pull it off! Thayil has used his creative imagination to add detail into the lives of the women who are all-too-briefly mentioned in the gospels. In addition to Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and other women whose names we know from the text, there are women who are anonymous in the gospel narratives but who are given names in this novel, either made up by Thayil himself or discovered by him somewhere in Christian tradition.

Thayil has also drawn on books outside the New Testament for his portrayal, in particular the apocryphal gospels, the Protevangelium (or Infancy Gospel of James) and the Gospel of Mary. Altogether, this suggested a very enticing package; Thayil was shortlisted for the Man Booker prize for another, earlier novel, Narcopolis (2012), and this latest one has received some very positive reviews already. So I ordered it without delay.

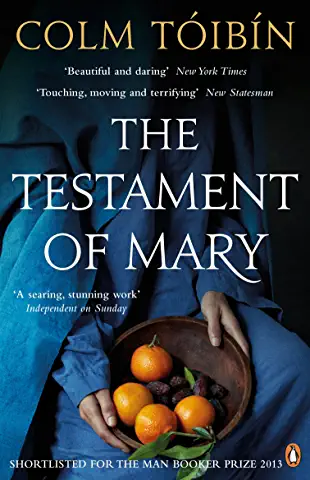

If I told you that I was very disappointed with the book, you might think it was just that my expectations had been raised too high and so the book fell short of what I might have hoped for. This happens when people strongly recommend films, doesn’t it? However, I can list some concrete reasons as to why I regarded it as so poor. One reviewer has praised Thayil for his theological knowledge; in my view, this was greatly lacking and I wondered if he had rushed the writing without sufficient research. It reminded me of another woeful book on this topic which achieved good reviews: The Testament of Mary by Colm Toíbín, for some reason shortlisted for the Man Booker prize in 2013. Am I the one with the problem?!

Let us start with three points that The Testament of Mary and Names of the Women have in common. First, they are both quite depressing, and express very little of the joy that one suspects would have been present at the very beginnings of Christianity. Both portray Jesus’ followers as single-minded, unkind zealots. I can’t imagine them converting anyone! I understand how Toíbín’s pessimistic view of Christianity might have arisen from his living in a twenty-first century Ireland recently shaken by the scandals of sex abuse by priests or members of religious orders, and of the infamous Magdalene laundries which enslaved and abused women for years because of perceived moral misdemeanours.

Thayil comes from the Syrian Christian tradition of Kerala, India, and he was educated in Jesuit schools. I don’t know how this has shaped his understanding of early Christianity. Certainly, he sets out to present a feminist corrective to the male-dominated accounts of the early Church, and of that I heartily approve. But I don’t think that he pays enough attention to the gospel passages which say that the women travelled with Jesus and contributed ‘out of their resources’, suggesting a far from passive and subordinate involvement in Jesus’ community.

Second, both of these novels portray a very unhappy Mary the mother of Jesus. In Toíbín’s novel, she remains wracked with the agony of the crucifixion and knows nothing of the ecstasy of the resurrection. In Thayil’s account, she is abandoned by everyone: her parents when they take her to the Temple, then by the Temple priests when they ask her to leave at a certain age (these details taken from the Protevangelium, not the gospels), and finally by Jesus himself, because his eyes are firmly set on the spiritual world of his divine Father. There is no angel of the Annunciation. In this novel, even the ‘handing over’ of Mary to the beloved disciple John at the crucifixion is the final rejection and misunderstanding of Mary by her son. This is not the Mary who sings, ‘My soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my saviour’.

And third, both novels narrate the gospel events pretty much as they are laid out in the Bible or apocryphal gospels. Thayil and Toíbín simply weave in extra stories and details around the biblical texts. This works in historical novels, such as The Girl with the Pearl Earring by Tracy Chevalier, when no-one doubts that Vermeer used a model for the painting and so Chevalier uses her imagination to flesh out the life story of the model. But it is not so easy with the Bible to assume that Jesus actually was born of a virgin, walked on water, or raised the dead. The gospels are not history as we understand it; there are many Christians who accept that the miracle stories ‘ain’t necessarily so’. And if one does believe that these things happened, then surely that is a foundation for a story of excitement and wonder, not one of a depressing all-too-earthly reality in which there is little joy.

Including the miraculous events of Jesus’ ministry just as the Bible describes them, but at the same dismissing the core theology of Christian belief, seems to me to be creating a plot with a mega great hole in it. The medium (the biblical narratives) and the message (the Christian faith) are integrated in the Bible; Thayil and Toíbín retain the medium but not the message. Thayil’s Jesus does not believe in forgiveness: that is ‘the recourse of the weak’. Oh. Thayil has reproduced many aspects of the gospel account in their original form but then cut out the best bits, like the Sermon on the Mount.

Take Lazarus. In both Toíbín’s and Thayil’s novels, he is raised from the dead by Jesus – as John chapter 11 describes – but then becomes a ghost-like depressive whose resurrection turns out to be rather unfortunate for him. I don’t know why Thayil repeated this theme from Toíbín’s book, as it is no longer original. But anyone with any sensitivity to the biblical traditions knows that the raising of Lazarus is a narrative which proclaims the eternal destiny of the one who believes in Jesus, whether you think that it happened historically or whether you think that it didn’t. It is the ‘sign’, as John’s Gospel puts it, that Jesus is the ‘resurrection and the life’. You really cannot have a depressed raised Lazarus. It simply doesn’t work. If Lazarus is raised, then we will all be raised; that sounds pretty OK to me and Lazarus was probably fairly upbeat about it. I personally don’t think that Lazarus was taken out of the tomb after four days: it is a parable, a metaphor. But I do believe in what it represents: the resurrection and the life.

An author with knowledge of biblical studies would know that there is a long scholarly tradition of people questioning and researching whether this or that event in the life of Jesus happened, or whether the story emerged later to make a point about the Christian faith. Given that both Toíbín and Thayil are critical thinkers, and have no problem with challenging cherished notions of the Christian tradition, they could have been more imaginative with reconstructing how the original story might have looked. What was the real life story of Jesus’ community that preceded the gospel traditions? And more relevant to Thayil’s novel, what was Jesus’ relationship to the women in the community? We get little sense of that, apart from some dreary sermons from the risen Jesus to Mary Magdalene that contain no hint of her response. What questions might she have had about what she heard?

Thayil paints the picture of a great gulf between Jesus and his family, including his mother. He has made a big meal of a particular passage in the synoptic gospels where Jesus does not receive his mother and brothers but instead refers to his followers as his true family. Yet this can be explained by the concern in the gospels to show new converts that they belong to Jesus’ family without being related to him or even sharing his ethnic identity. There are several other passages where it is clear that Jesus’ family were important in the early Church. John 2 (the wedding at Cana) has the family journeying together (but not Joseph, who is presumed to have died); Acts 1 has Mary and Jesus’ brothers together with the disciples after the ascension of Jesus; Acts 15 along with Galatians 1-2 shows that Jesus’ brother James had an important leadership role in the early Church. He was probably Jesus’ intended successor, as is suggested in the Gospel of Thomas. Thayil has no interest in the importance of James because it doesn’t suit his image of a distanced and neurotic Jesus, who has little interest in anything but his heavenly destination. In particular, Thayil’s Jesus abandons the females in his family, his mother and two sisters (we do not actually know how many sisters there were from the gospel accounts). All three are very sad characters.

That is certainly not the picture of Jesus that I hold in my mind, so I wonder why Thayil wants him to be like that, and why his reviewers rate it so highly. My own conclusion is simply that Thayil wants to be controversial, sell a few books, and win a few admirers in the literary circuit who like something subversive. He could have written an interesting novel about the women around Jesus without resorting to these tactics and achieved his original brief more directly: giving the women in the gospels a voice. None of them in his reconstruction come up with very much in the way of insight about the theology and belief that is about to shake the world. Everything that Mary Magdalene knows is told to her by Jesus. Thayil’s women are, in the main, victims or carried along by the tide of events.

Another trick that he misses is that he could have done more with the Gospel of Mary, an incomplete text discovered in 1896 after centuries of being lost. After all, he has this book in his mind: Mary Magdalene emerges in his re-telling of the story as the one person in true contact with the risen Jesus, just as she is in the Gospel of Mary. Yet the points of contact between Names of the Women and the Gospel of Mary are limited to just one: Jesus states that he doesn’t believe in sin. In Thayil’s novel, Jesus says that ‘there is no sin but ignorance’, while in the Gospel of Mary, Jesus says that there is no sin, only the sin that human beings cause to exist. So the intersections between them are tangential; I think this was a missed opportunity. A novel which imagined some kind of original experience for Mary Magdalene which gave rise to the Gospel of Mary with a clearer connection would have been interesting.

Overall, my estimate as someone who has been interested in the role of women in the gospels for some time is that Thayil has fallen a long way short of what is possible with the subject matter. Christians will find his novel too dispiriting; atheists will wonder why the Bible characters are being revisited yet again; feminists might approve of the fact that the attempt to paint portraits of the gospel women has been made in mainstream fiction, but I doubt whether Thayil’s images will inspire them much. Jesus is still the miracle-working superstar, and I would argue that reclaiming the contribution of women to his ministry needs much stronger female characters than these.

Comments